Overview

Today we cover the third effect in the individual demand function: the (own) price effect, aka the law of demand: how changes in a good’s (own) price affect quantity demanded for that good.

We introduce the idea of (simplified, own-price) demand functions, inverse demand functions, and a demand curve. I will also show you examples of how we derive demand functions and curves.

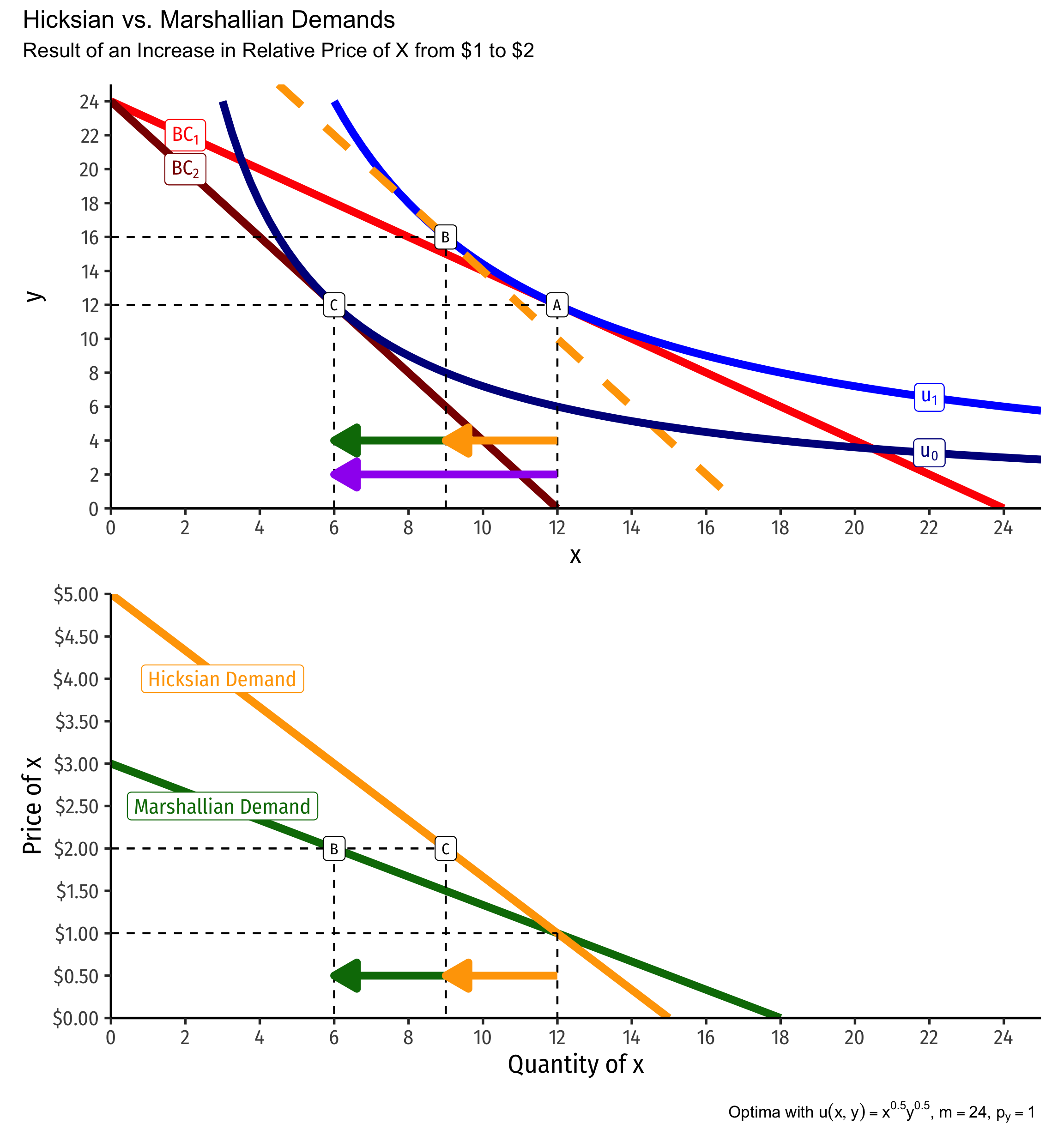

The other major concept today is breaking apart the law of demand into two effects: the (real) income effect, and the substitution effect. We considering them conceptually and graphically. These can be a difficult concept for students to grasp.

Slides

Below, you can find the slides in two formats. Clicking the image will bring you to the html version of the slides in a new tab. Note while in going through the slides, you can type h to see a special list of viewing options, and type o for an outline view of all the slides.

The lower button will allow you to download a PDF version of the slides. I suggest printing the slides beforehand and using them to take additional notes in class (not everything is in the slides)!

Problem Set 1 Due Wednesday February 16

Problem set 1 (on 1.1-1.4) is due by class time Wednesday February 16.

Problem Set 2 Due Monday February 21

Problem set 2 (on classes 1.5-1.7) is due by class time on Monday, February 21.

Interactive Examples

- Visualizing the Consumer’s Problem

- Visualizing Changes in the Consumer’s Problem

- Visualizing Demand Shifters

These are examples that I wrote in R/Shiny in the past, to visualize what it is we are looking at. As I find more time, I will update these and integrate them into our slides, but until then, I will just post links.

The first is a visual example of the static (one-time) Consumer’s problem. You can adjust things about the (Cobb-Douglas) utility function, income, and prices, and see how it would affect the graph and the optimum.

The second is a visual example of dynamic changes in the Consumer’s problem. The consumer starts at a pre-defined optimum. You can adjust any of the budget constraint parameters , and see how it would affect a new optimum, which you can compare the the original optimum.

The third is a visual example of a hypothetical demand function for beer, with preference intensity, income, price of nachos (a complement), and price of wine (a substitute) as inputs to the function. Based on some pre-defined functions (in the background), you can change any of the inputs and see how it would affect the (inverse) demand function, expressed as a simple demand curve.

I hope some time to clean these up and make a few more, such as “Visualizing the Income and Substitution Effects” and “Estimating a Demand Function from Real World Data.”

Appendix

Example Demand Functions

The examples below show how we can take a utility function and derive a demand function.

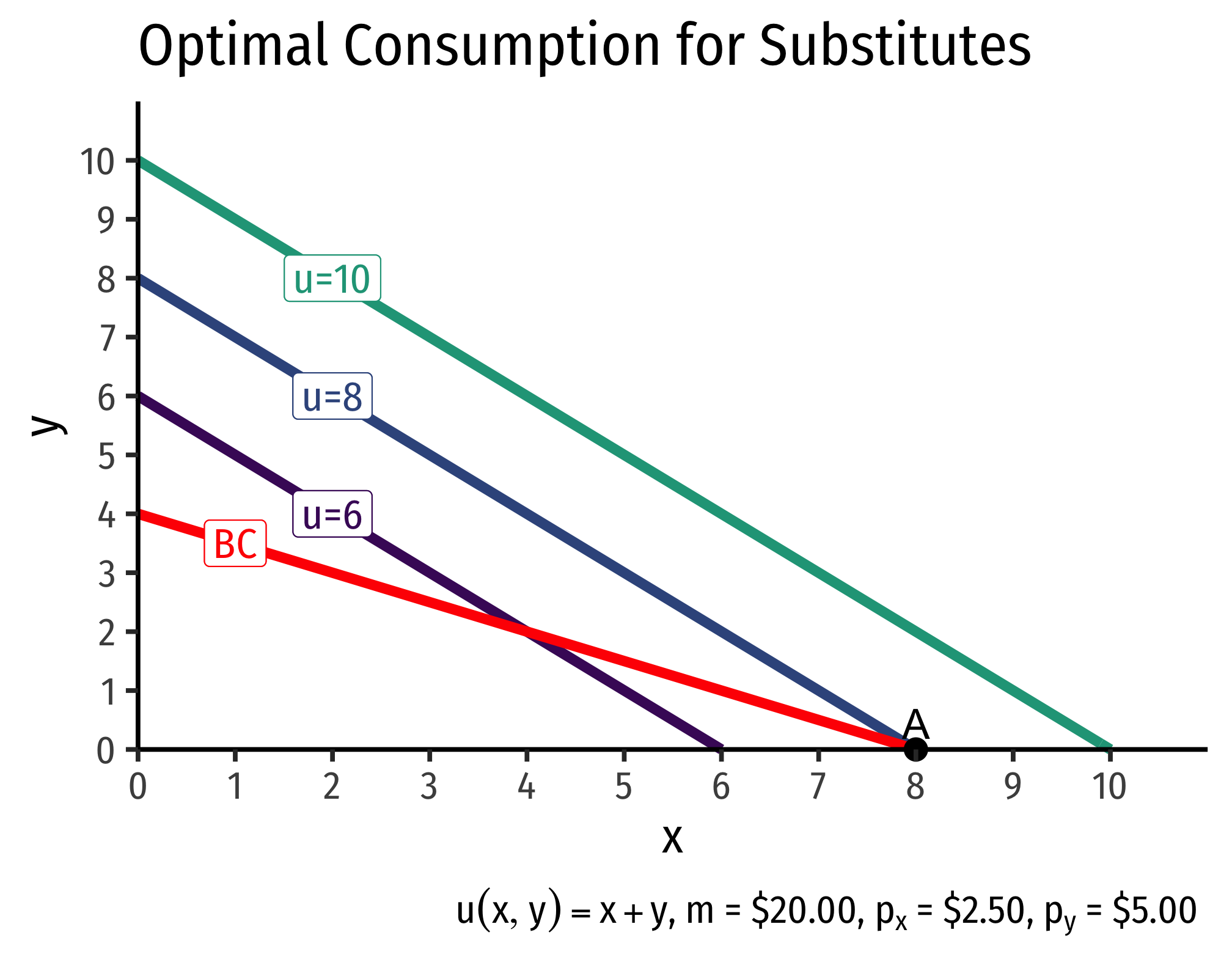

Perfect Substitutes

Recall that perfect substitutes have indifference curves that are straight lines (constant MRS), and have a utility function of:

Since both the budget constraint and the indifference curves are straight lines, we will not have a point of tangency between them, but a point(s) where the lines intersect.

There are three possible cases,

- if , the slope of the budget constraint is flatter than the slope of the indifference “curves.” The optimal bundle is spending all income on good .

- if , the slope of the budget constraint is steeper than the slope of the indifference “curves.” The optimal bundle is spending all income on good .

- if , the budget constraint and indifference “curves” are the same line, so any point on the lines is optimal!

The first two cases are known as “corner solutions,” where a consumer chooses all of one good, and none of another. Note perfect substitutes are not convex, and violate the assumption that “averages are preferred to extremes.”

We can therefore write the demand function for good x (and similarly for y):

On the graph above, since , the optimal consumption bundle is to spend all income on at (8,0), point A.

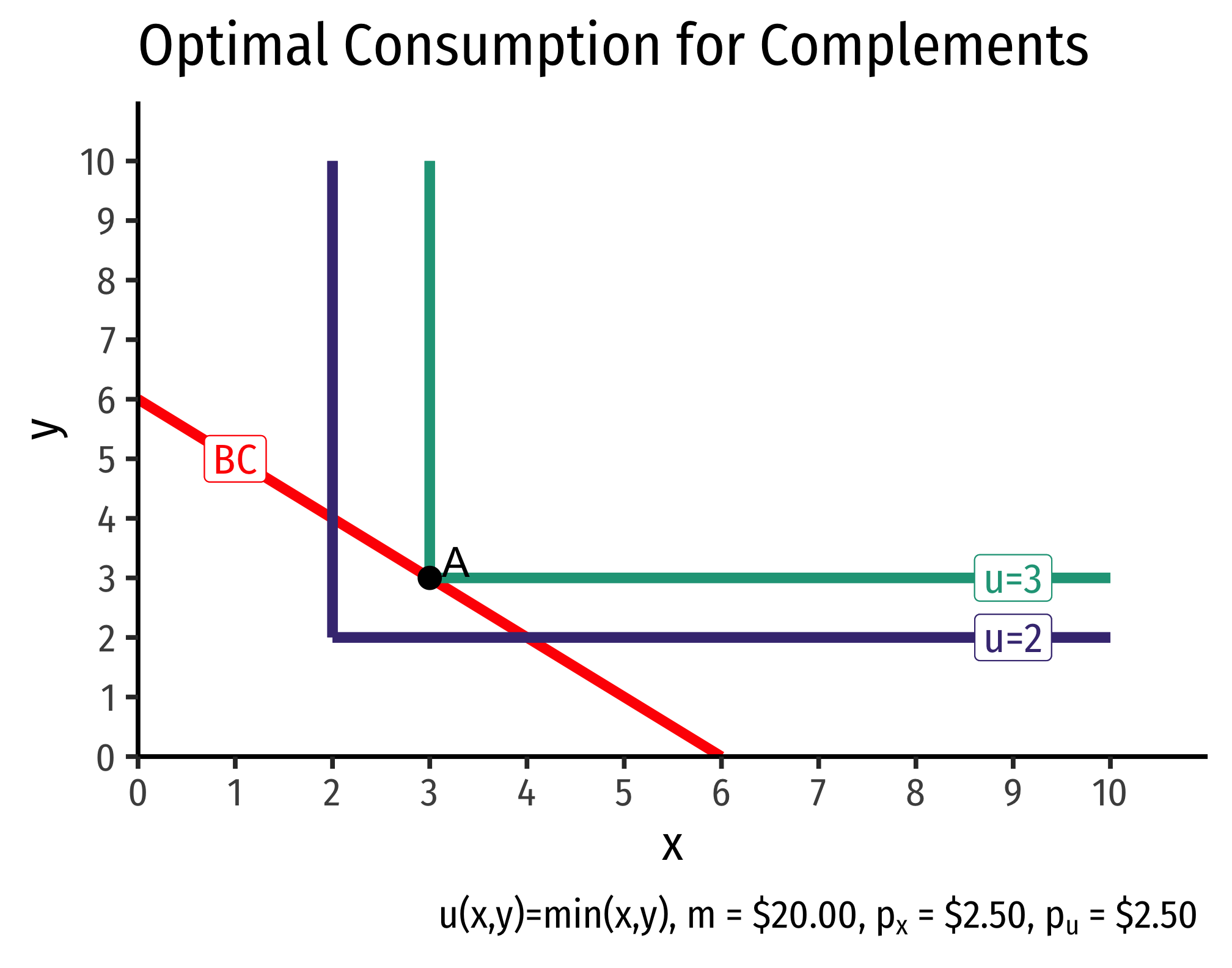

Perfect Complements

Recall that perfect complements have indifference curves that are right angles, and have a utility function of:

The optimal choice must always be at the corner of the indifference “curves.”

The consumer is purchasing equal amounts of and in this example, no matter what the prices are of either, so . We must satisfy the budget constraint, that (recall ). Solving this for gives us the demand function for good x:

This should be intuitive: the consumer must always purchase equal amounts of and , so it’s as if the consumer was spending all of their income on a single good that has a price of .

Cobb-Douglas

Now we come to a more realistic demand function. If a consumer has a Cobb-Douglas utility function1

Then we are solving the following constrained optimization problem:

I will solve this using the Lagrangian method.2

The First Order Conditions are:

Rearranging the first two FOCs:

Adding them together:

Solving for :

Substitute this back into each of the first two FOCs and solve for and , respectively, to get:

These are the demand functions for goods and . One of the convenient properties of Cobb-Douglas preferences is that a consumer spends a constant fraction of income on good , and the complement fraction on good !^This becomes especially simple when the exponents , as in:

So and are proportions of !

For a constant value of , this is a linear function of . So doubling, tripling, etc. will double, triple, etc. quantity demanded for . So the income expansion path is a straight line through the origin with a slope .

EXAMPLE

Suppose a consumer has a utility function

and faces constraints of , , .

Write the Lagrangian (and taking logs of the objective function, for simplicity):

FOCs are:

Rearrange the first two FOCs:

Add then together, and solve for :

Now substitute lambda into each of the first two FOCs, solving for and , respectively:

This consumer buys 2.5 units of at 25) and 5 units of at 25), spending all $50.

Recall the utility function is

Note the Cobb-Douglas exponents on and are equal and sum to 1: and . So the consumer spends of her income on , and on .

To get the demand functions for and , go back to the FOCs, and keep all budget constraint terms as variables .

Rearrange the first two FOCs:

Add then together, and solve for :

Substitute this back into each of the first two FOCs and solve for , and , respectively, to get:

These are the demand functions for and for .3

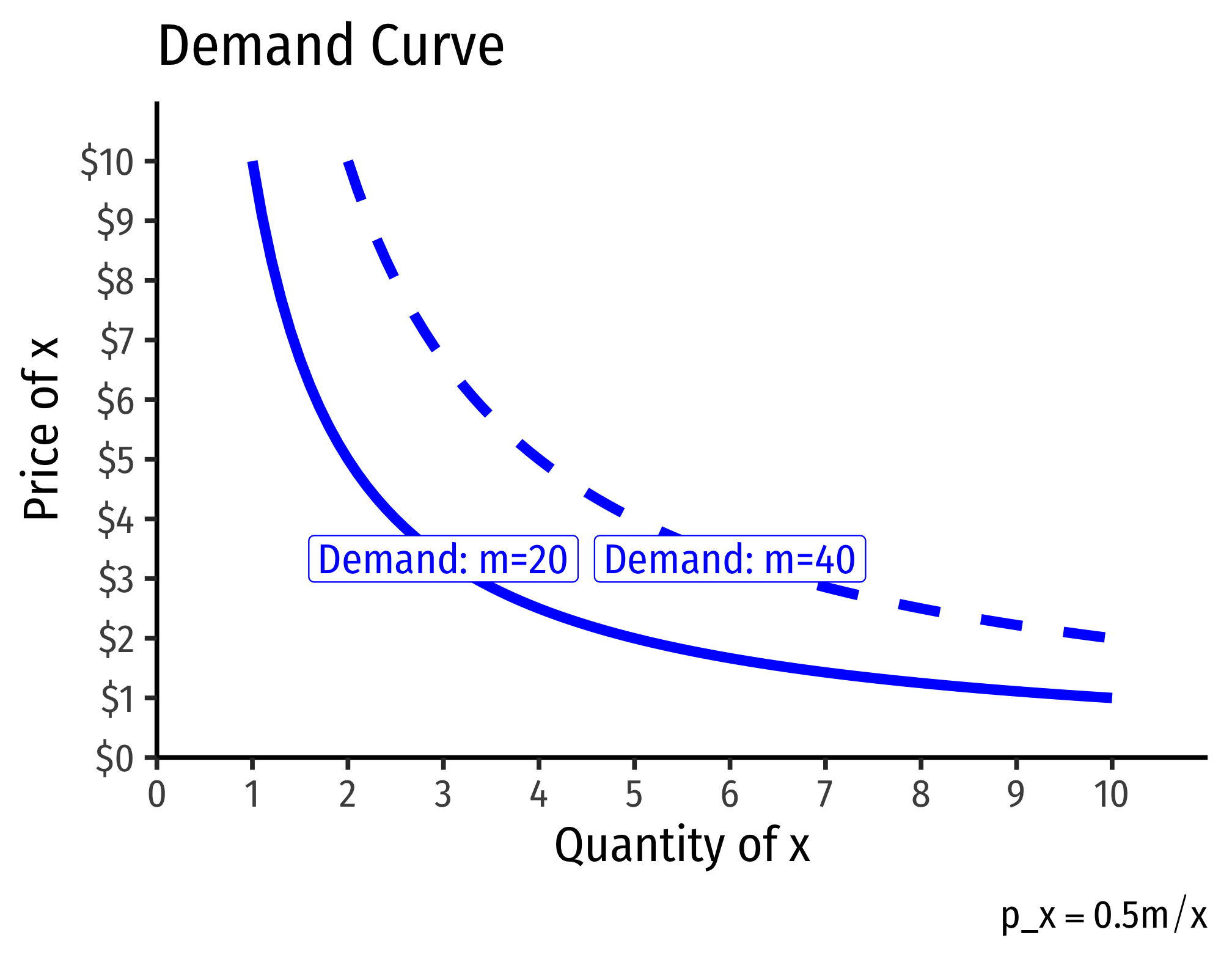

Note if we want to graph this, we need to find the inverse demand function by solving for :

Now we can graph a demand function for a given amount of income. As income changes, the demand curve shifts. Here are two examples, one where and another where :

Note: Natural logs are easier to work with, this function is equivalent to .↩︎

Note you could solve this by substitution. Use the definition of the optimum, that , plug in, and solving carefully for .↩︎

Note you can just take the rule learned above, that and and plug in and .↩︎