4.4 — Imperfect Competition

ECON 306 • Microeconomic Analysis • Spring 2022

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/microS22

microS22.classes.ryansafner.com

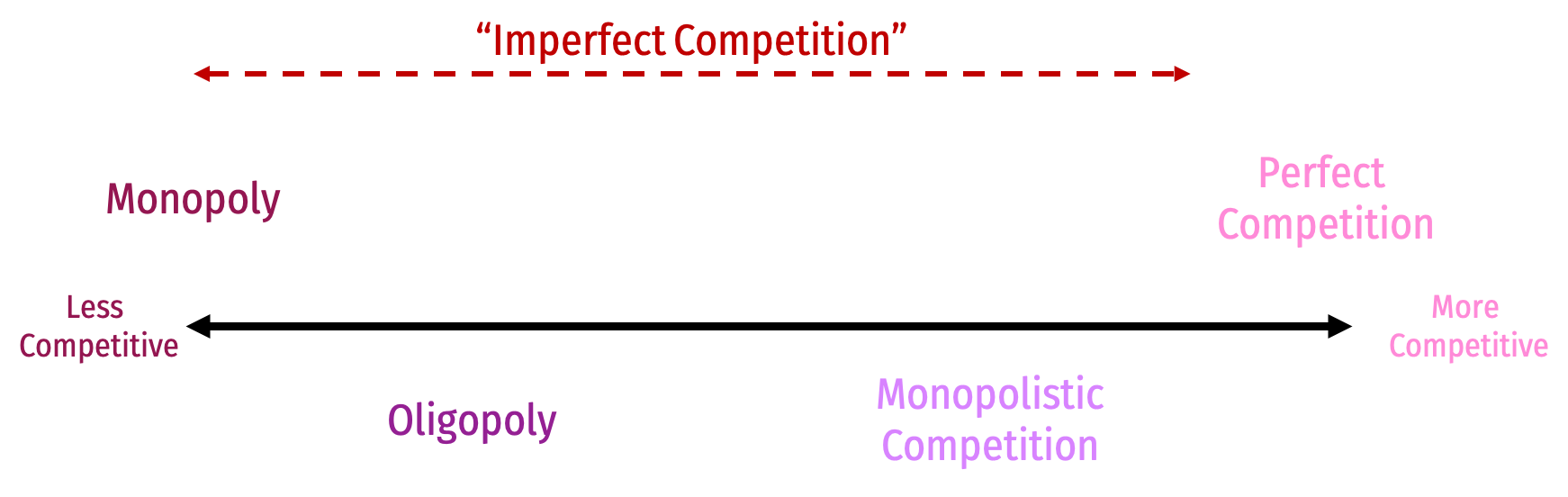

Reminder: Imperfect Competition

Monopolistic Competition

Monopolistic Competition

Monopolistic competition: each firm has some market power, but, the industry has free entry and exit (no barriers to entry)

- Each firm faces its own downward-sloping demand

- Firms are price-searchers

Model as a hybrid of monopoly and perfect competition models

Monopolistic Competition: Product Differentiation

Product differentiation: firms’ products are imperfect substitutes

Consumers recognize non-price differences between sellers’ goods

- Brand name & reputation

- Customer service

- Product features, shape, color, etc.

- Marketing

- Location, convenience

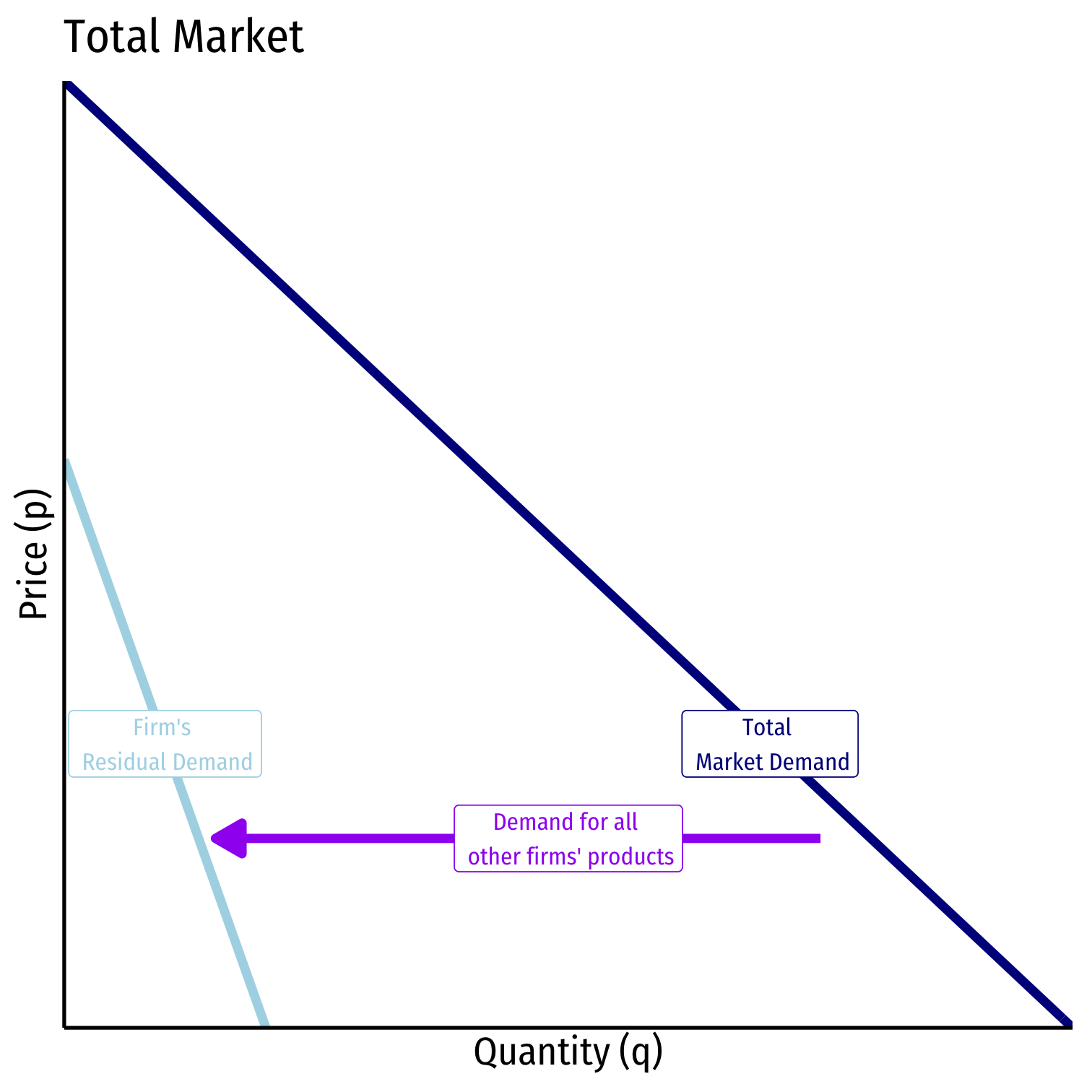

Monopolistic Competition: Residual Demand

Each firm faces own downward-sloping “residual” demand for each firm’s products

- Firm faces market demand (for broad product) leftover from all other firms’ sales

Example: demand for Lenovo laptops ≈ demand for laptops − laptops supplied by Acer, Asus, Apple, Dell, etc.

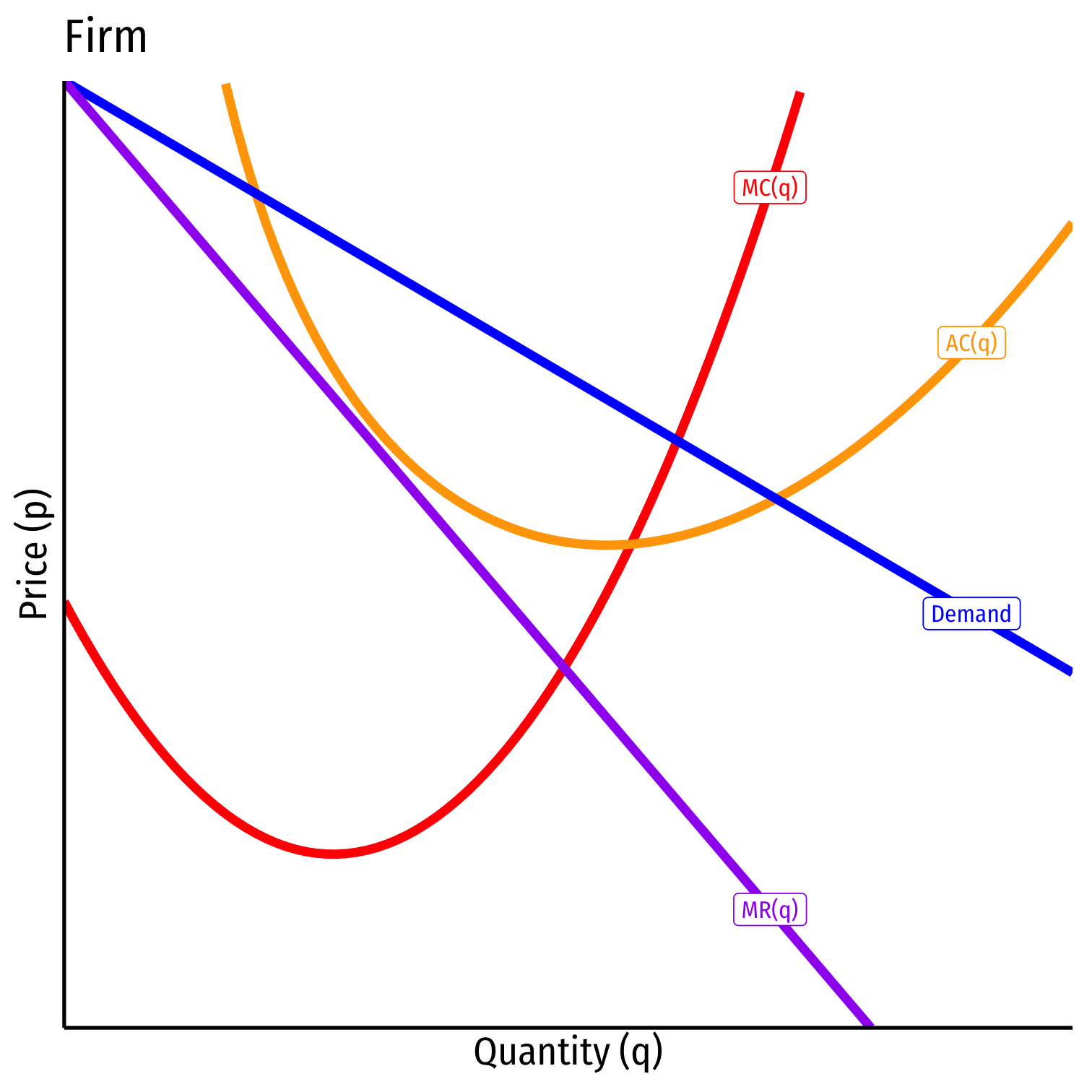

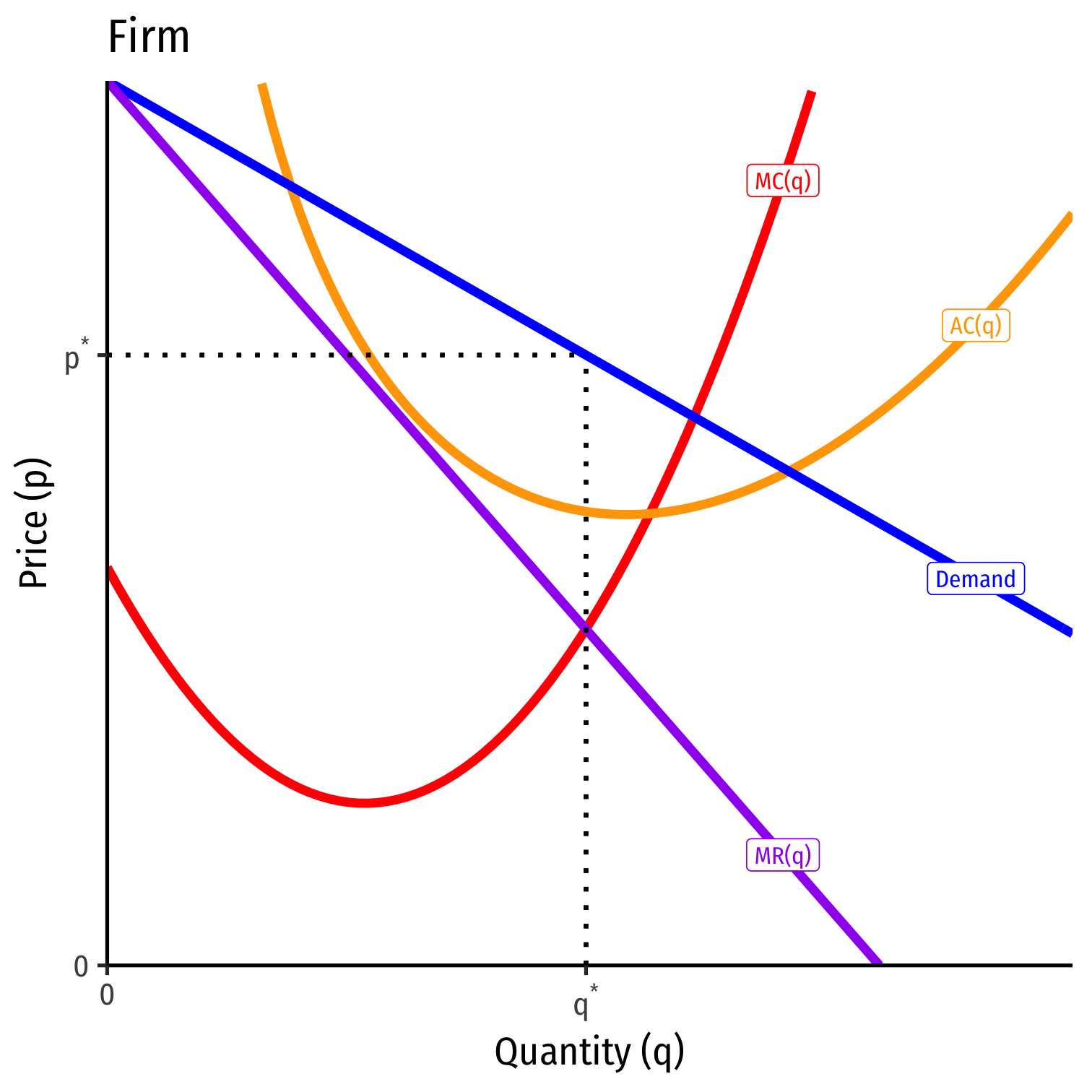

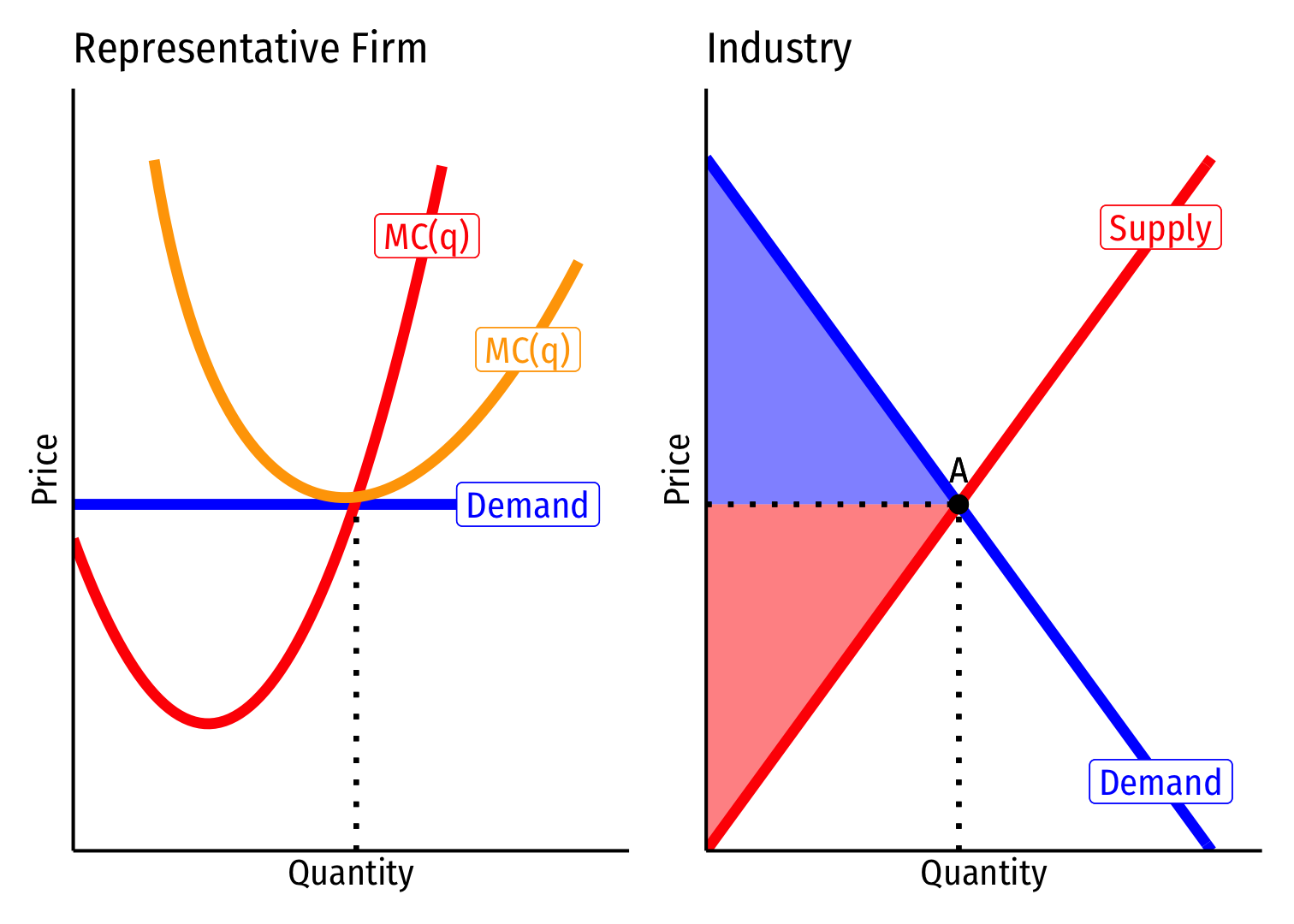

Monopolistic Competition Model: Short Run

- Short Run: model firm as a price-searching monopolist:

Monopolistic Competition Model: Short Run

Short Run: model firm as a price-searching monopolist:

q∗: where MR(q)=MC(q)

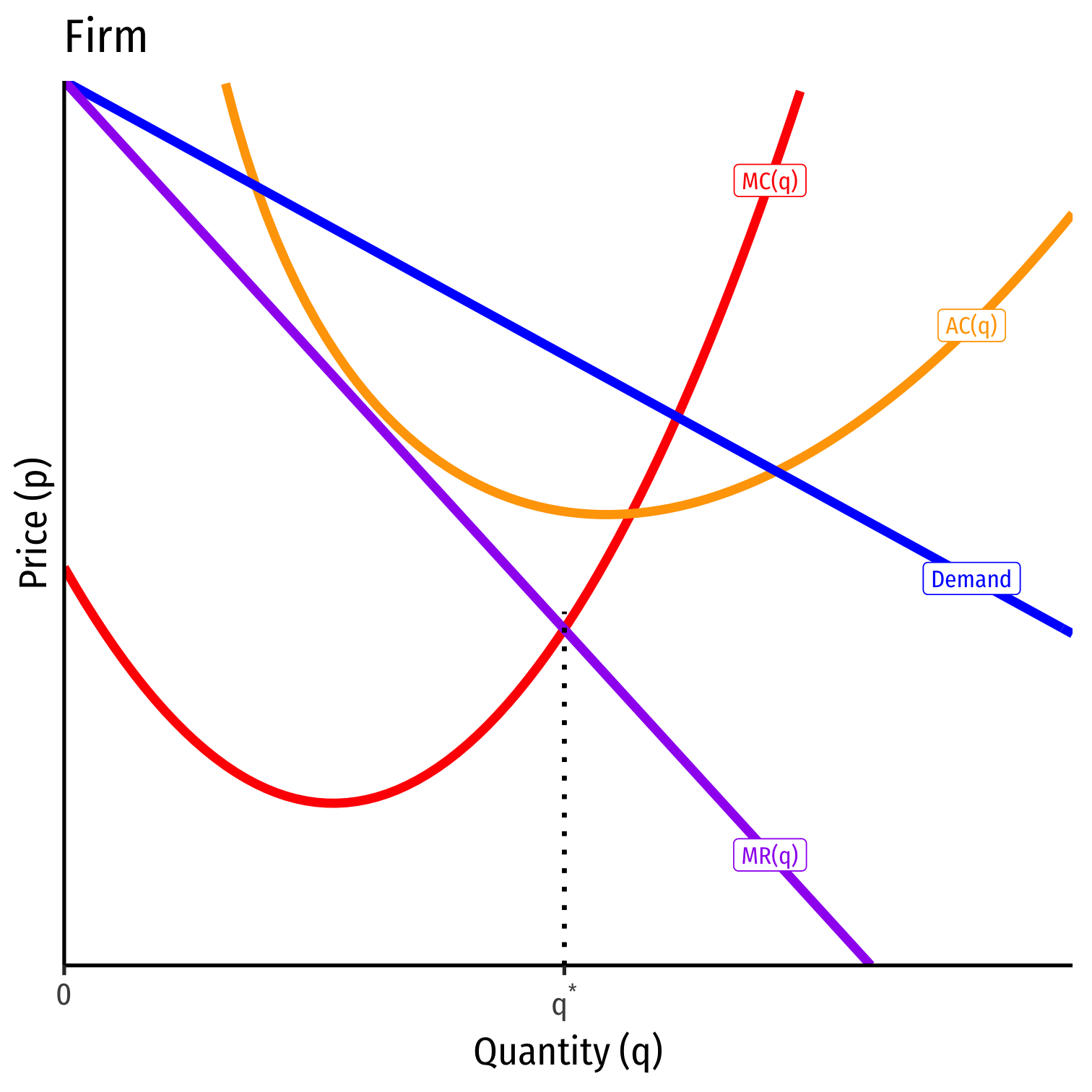

Monopolistic Competition Model: Short Run

Short Run: model firm as a price-searching monopolist:

q∗: where MR(q)=MC(q)

- p∗: at market demand for q∗

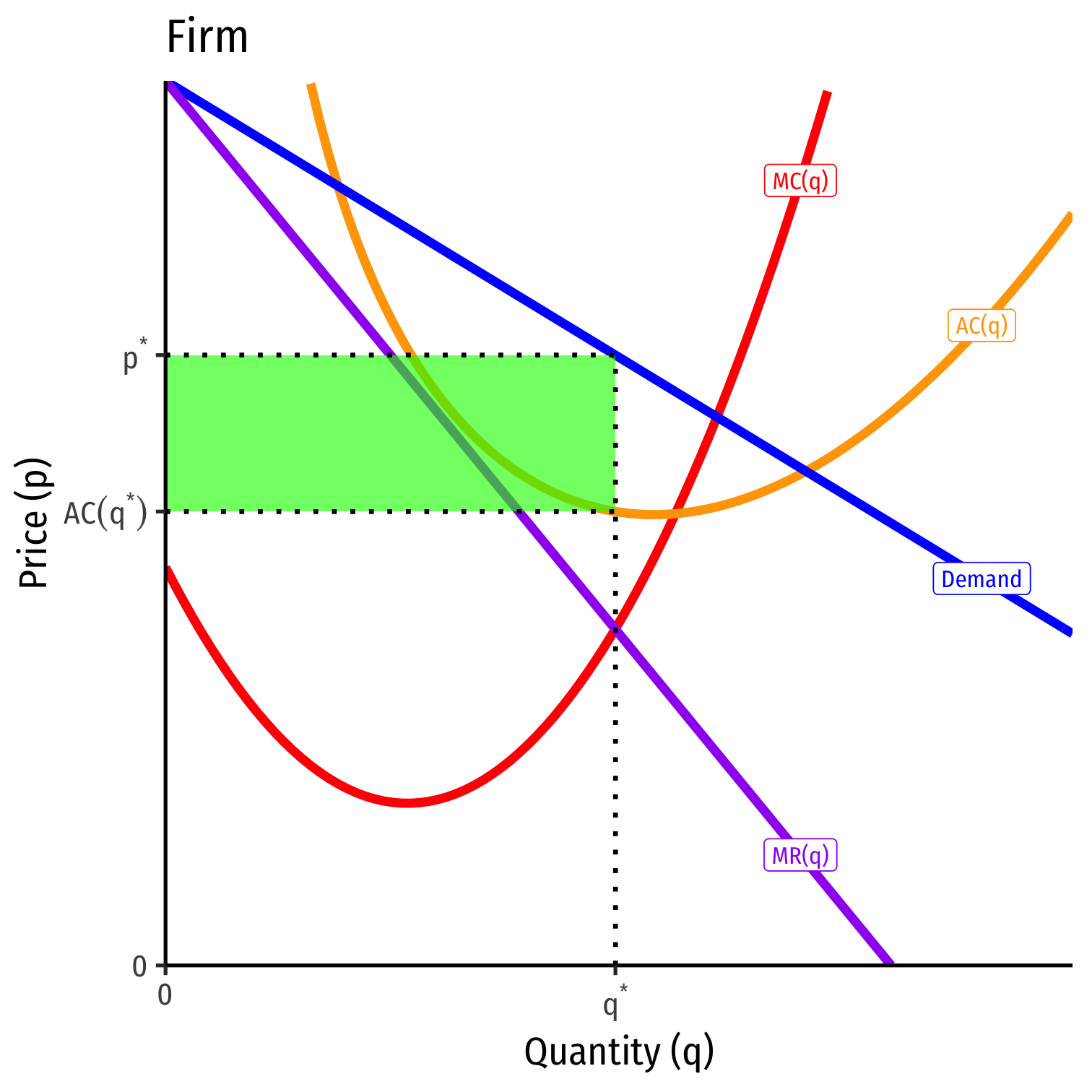

Monopolistic Competition Model: Short Run

Short Run: model firm as a price-searching monopolist:

q∗: where MR(q)=MC(q)

- p∗: at market demand for q∗

- Earns π=[p∗−AC(q∗)]q∗

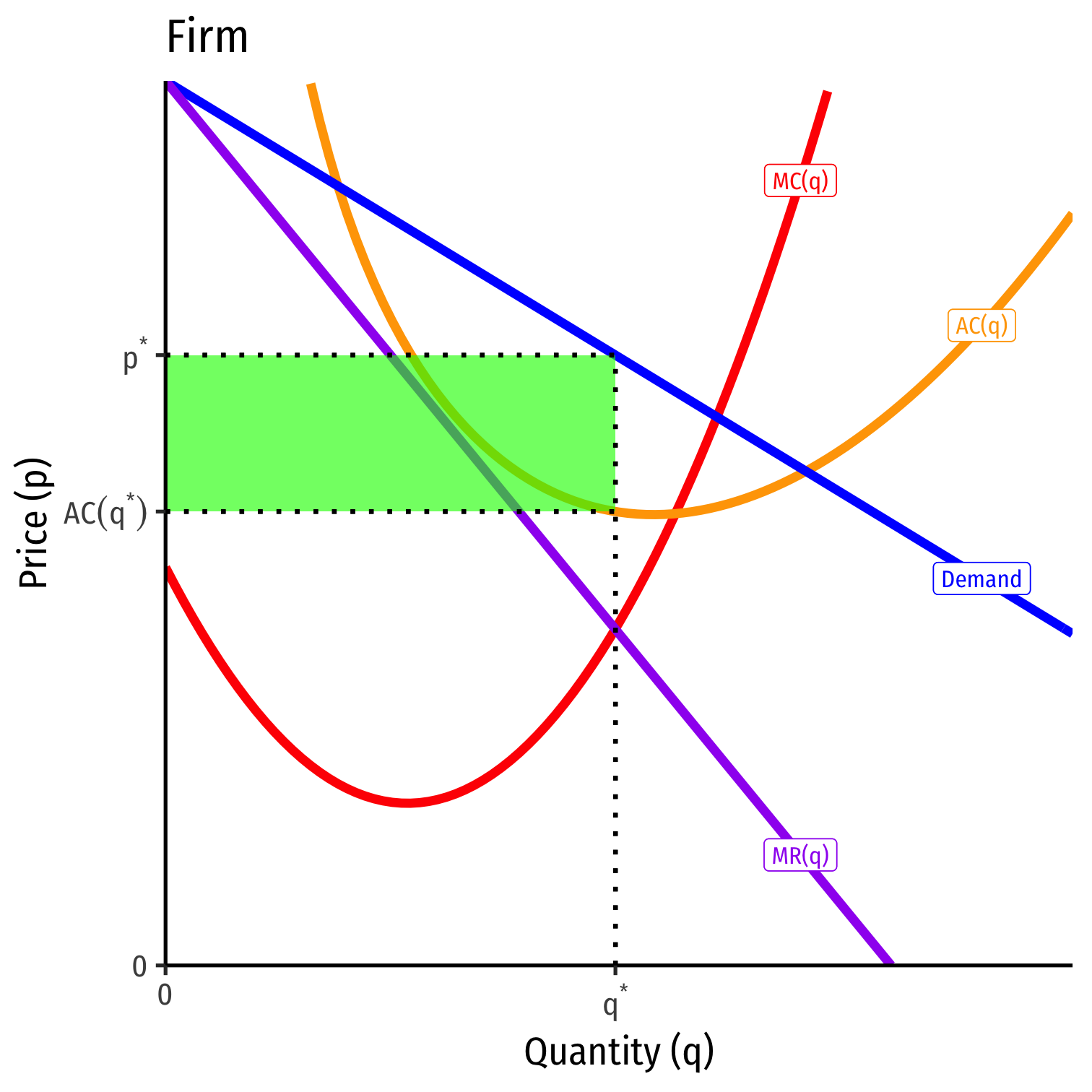

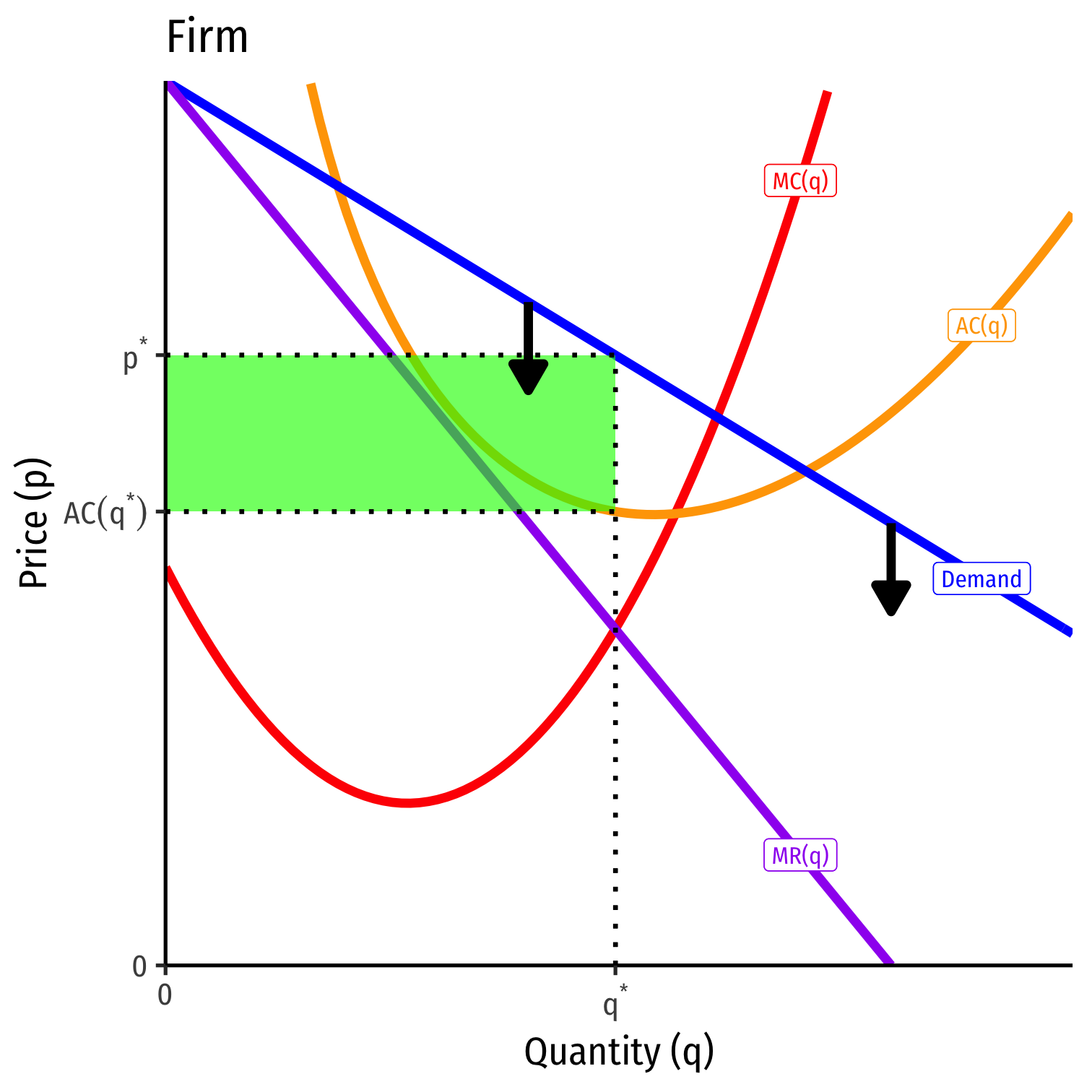

Monopolistic Competition Model: Long Run

Long Run: market becomes competitive (no barriers to entry!)

π>0 attracts entry into industry

Monopolistic Competition Model: Long Run

Long Run: market becomes competitive (no barriers to entry!)

π>0 attracts entry into industry

Residual demand for each firm’s product:

- decreases (more output by other firms)

- become more elastic (more substitutes from new competitors)

- until...

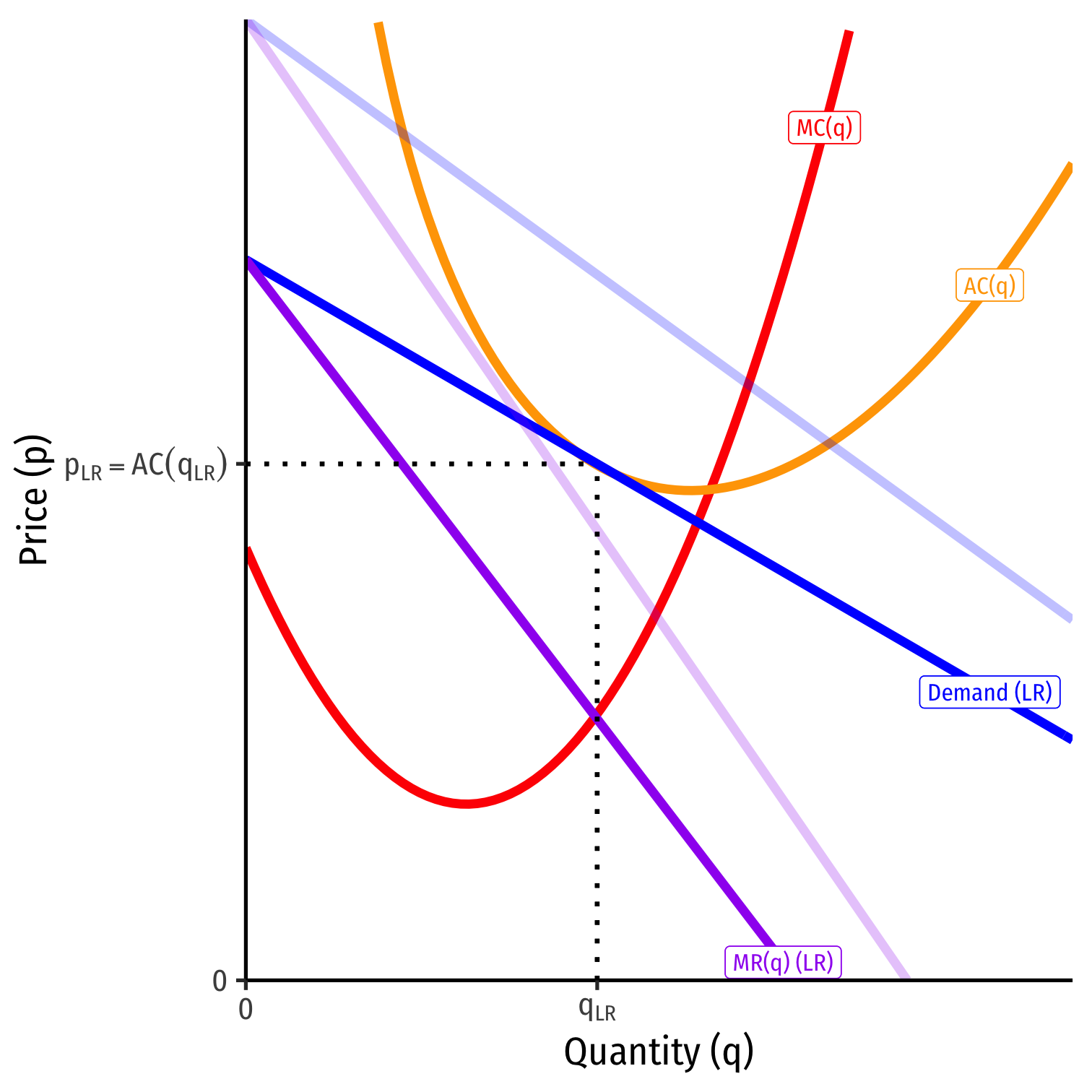

Monopolistic Competition Model: Long Run

† Note it is not at the minimum of AC(q)!

Long Run: market becomes competitive (no barriers to entry!)

π>0 attracts entry into industry

Residual demand for each firm’s product:

- decreases (more output by other firms)

- become more elastic (more substitutes from new competitors)

Long run equilibrium: firms earn π=0 where p=AC(q)

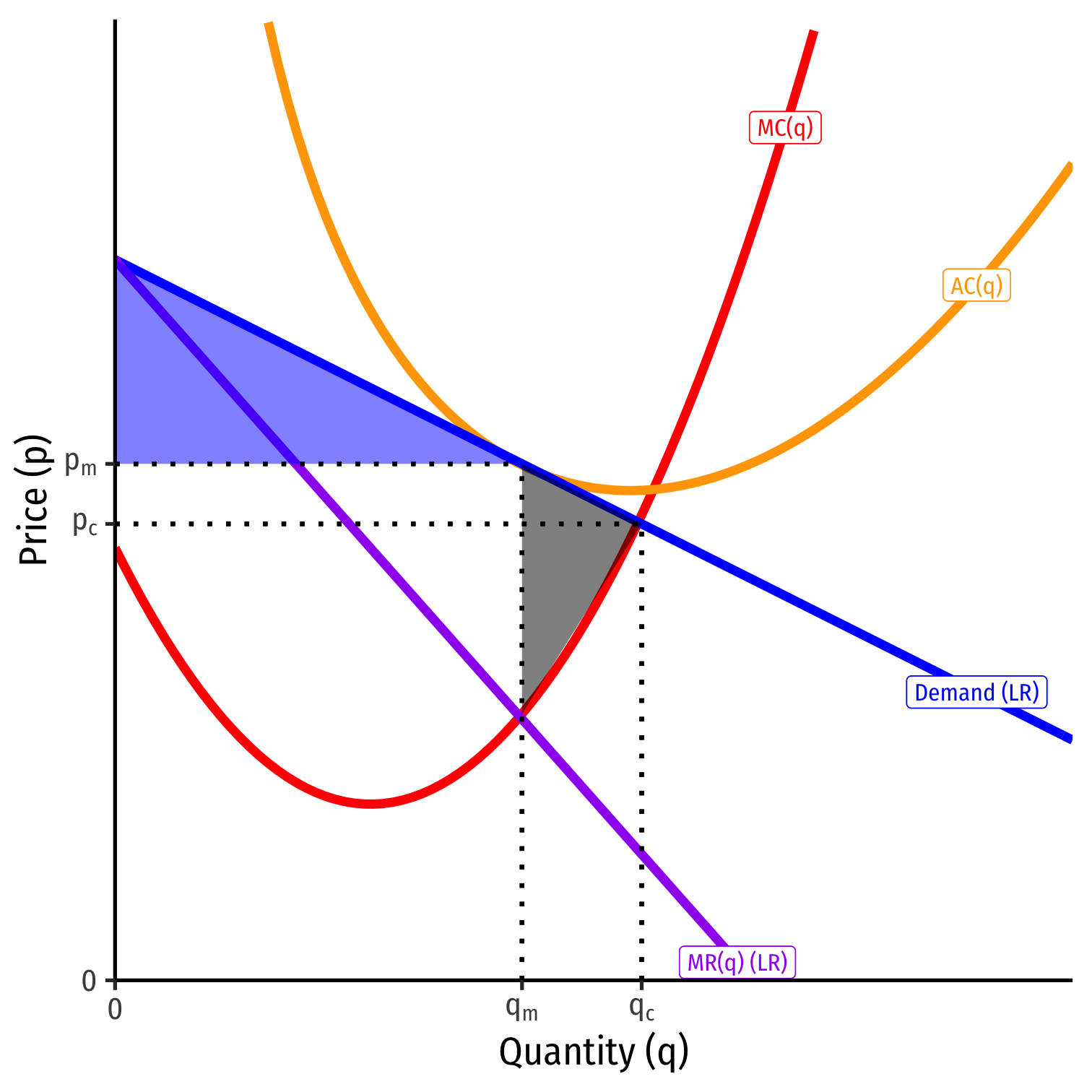

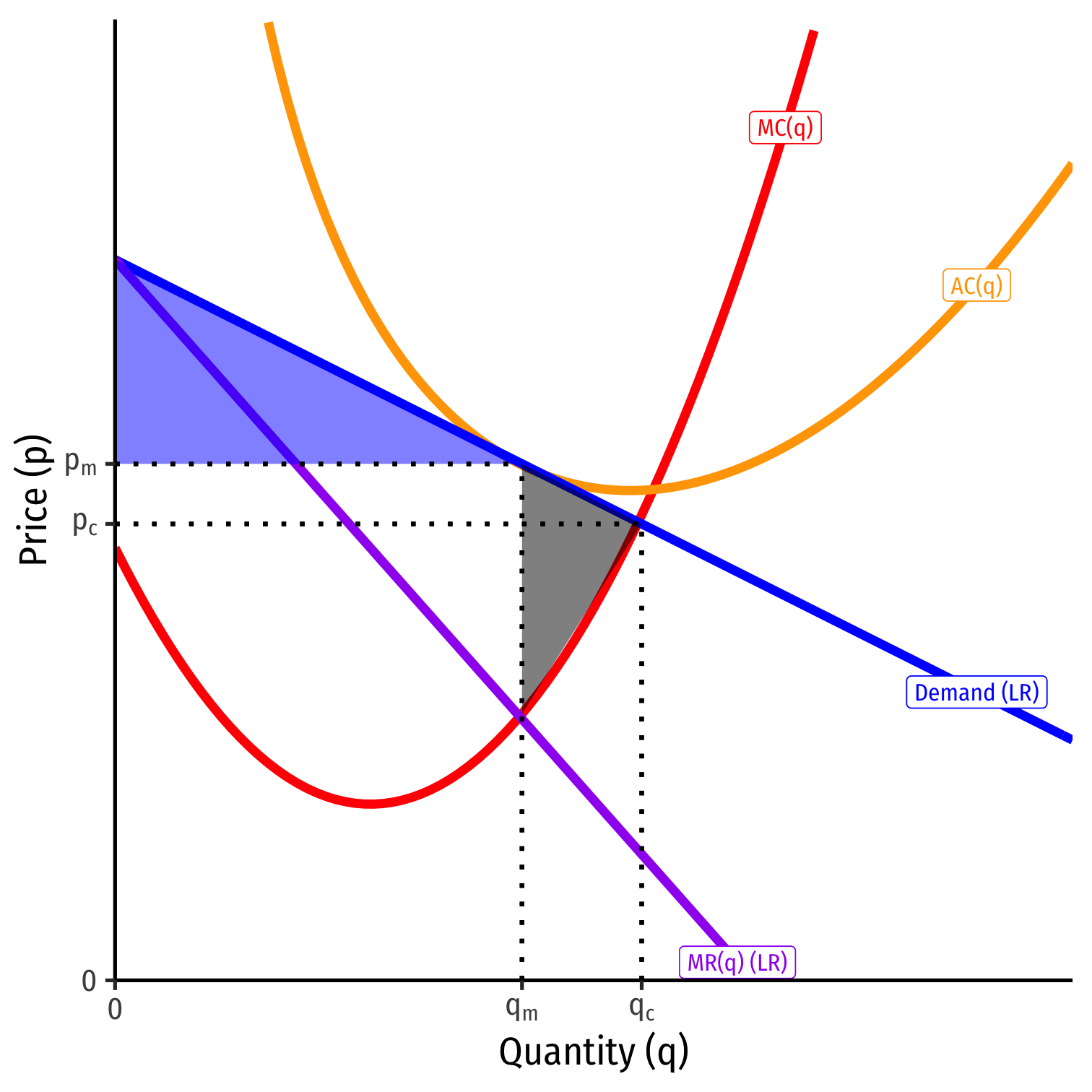

Monopolistic Competition vs. Perfect Competition

Perfect competition (qc,pc)

qc where P=MC(q)

pc=AC(q)min, productively efficient

pc=MC(q), allocatively efficient

- Maximum consumer surplus (and producer surplus)

- No DWL

Monopolistic Competition vs. Perfect Competition

Monopolistic competition (qm,pm)

qc>qm, where MR(q)=MC(q)

pm=AC(q)

- but not ACmin, so some productive inefficiency

pm>MC(q), allocative inefficiency

- Less Consumer Surplus

- Deadweight loss

Monopolistic Competition vs. Perfect Competition

Like a monopoly, produces less q at a higher p than competition, some DWL

But like perfect competition, still no π in the long run!

Outcome is between perfect competition & monopoly in terms of efficiency & social welfare

Oligopoly

Oligopoly

Oligopoly: industry with a few large sellers with market power

Other features can vary

- May sell similar or different goods

- May have barriers to entry

Key: Firms make strategic choices, interdependent on one another

For modeling simplicity:

- Duopoly: a market with 2 sellers

Oligopoly: Modeling

Unlike perfect competition or monopoly, no single “theory of oligopoly”

Depends heavily on assumptions made about interactions and choice variables (FYI):†

- “Bertrand competition:” firms compete on price

- “Cournot competition:” firms simultaneously compete on quantity

- “Stackelberg competition:” firms sequentially compete on quantity

One certainty: oligopoly is a strategic interaction between few firms

Game Theory

- Game theory: a set of tools that model strategic interactions (“games”) between rational agents, 3 elements:

- Players

- Strategies that each player can choose from

- Payoffs to each player that are jointly-determined from combination of all players’ strategies

Game Theory vs. Decision Theory Models I

Traditional economic models are often called “Decision theory”:

Optimization models ignore all other agents and just focus on how can you maximize your objective within your constraints

- Consumers max utility; firms max profit, etc.

Outcome: optimum: decision where you have no better alternatives

Game Theory vs. Decision Theory Models I

Traditional economic models are often called “Decision theory”:

Equilibrium models assume that there are so many agents that no agent’s decision can affect the outcome

- Firms are price-takers or the only buyer or seller

- Ignores all other agents’ decisions!

Outcome: equilibrium: where nobody has any better alternative

Game Theory vs. Decision Theory Models III

Game theory models directly confront strategic interactions between players

- How each player would optimally respond to a strategy chosen by other player(s)

- Lead to a stable outcome where everyone has considered and chosen mutual best responses

Outcome: Nash equilibrium: where nobody has a better strategy given the strategies everyone else is playing

Equilibrium in Oligopoly

What does “equilibrium” mean in an oligopoly?

In competition or monopoly, a unique (q∗,p∗) for industry such that nobody has incentives to change price

Equilibrium in Oligopoly

- Oligopoly: use game-theoretic Nash Equilibrium:

- no player wants to change their strategy given all other players’ strategies

- each player is playing a best response against other players’ strategies

As a Prisoner's Dilemma I

Example: suppose we have a simple duopoly between Apple and Google

Each is planning to launch a new tablet, and choose to sell it at a High Price or a Low Price

As a Prisoner's Dilemma I

- Payoff matrix represents profits to each firm

- First number in each box goes to Row player (Apple)

- Second number in each box goes to Column player (Google)

As a Prisoner's Dilemma II

- From Apple's perspective:

- Low Price is a dominant strategy for Apple

Apple's best responses

As a Prisoner's Dilemma II

- From Google's perspective:

- Low Price is a dominant strategy for Google

Google's best responses

As a Prisoner's Dilemma II

- Nash equilibrium: (Low Price, Low Price)

- neither player has an incentive to change price, given the other's price

Nash equilibrium

As a Prisoner's Dilemma III

Nash equilibrium: (Low Price, Low Price)

- neither player has an incentive to change price, given the other's price

A possible Pareto improvement: (High Price, High Price)

- Both players are better off, nobody worse off!

- Is it a Nash Equilibrium?

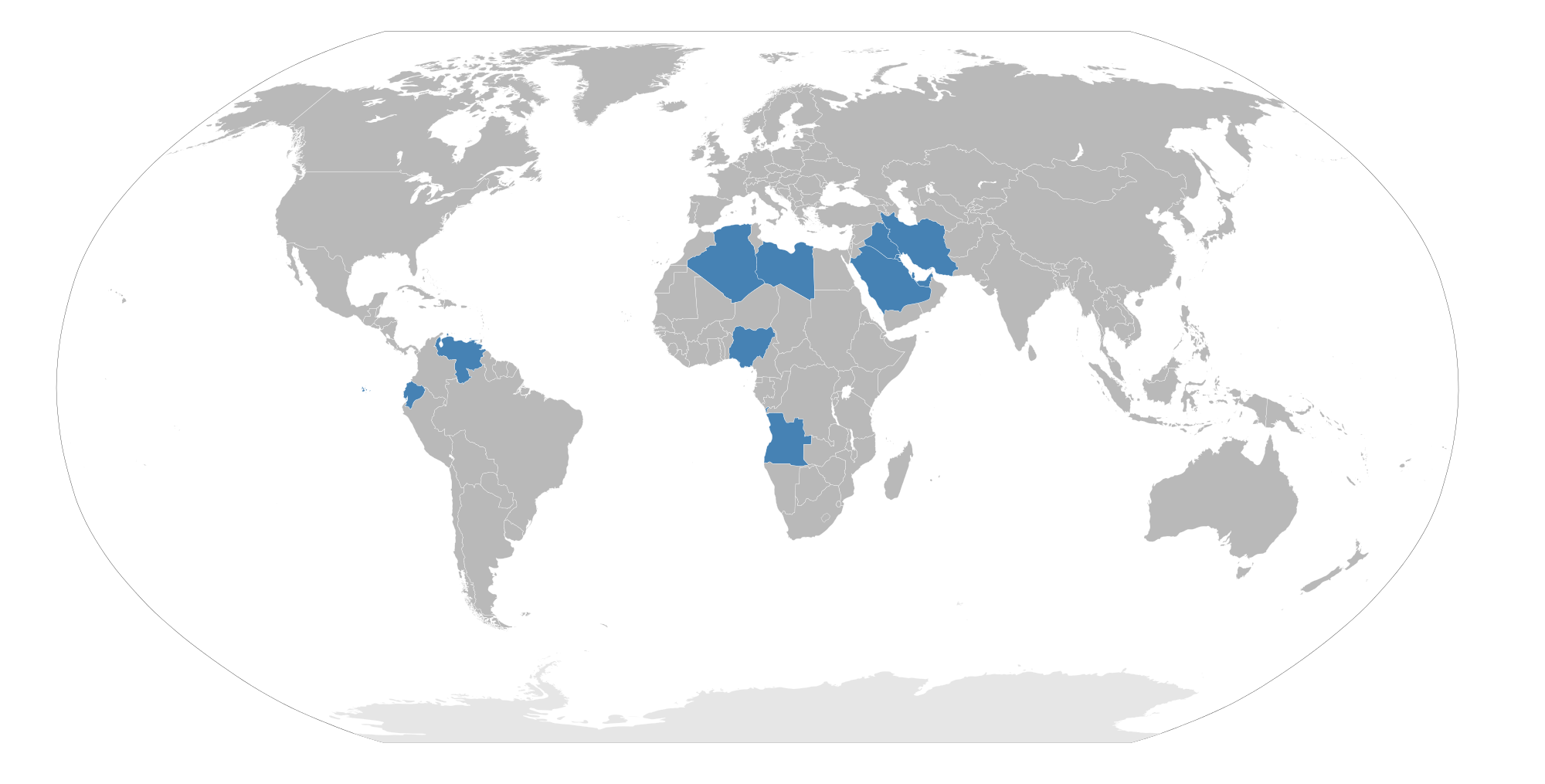

Cartels

As a Prisoner's Dilemma IV

Google and Apple could collude with one another and agree to both raise prices

Cartel: group of sellers coordinate to raise prices to act like a collective monopoly and split the profits

Instability of Cartels

Cartels often unstable:

Incentive for each member to cheat is too strong

Entrants (non-cartel members) can threaten lower prices

Difficult to monitor whether firms are upholding agreement

Cartels are illegal, must be discrete

Attempts to Sustain Collusion I

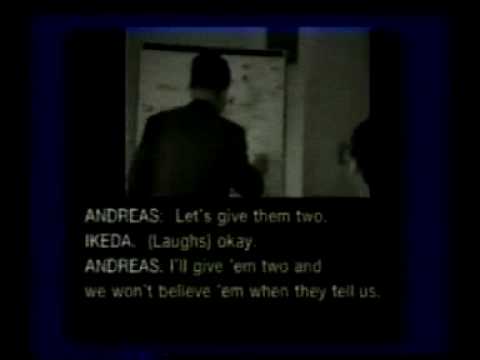

Archer Daniels Midland (USA), Ajinomoto (Japan), Koywa Hakko Kogyo (Japan), Sewon American Inc (South Korea) held secret meetings to fix the price of lysine, a food additive to animal feed in the 1990s.

Attempts to Sustain Collusion I

Archer Daniels Midland (USA), Ajinomoto (Japan), Koywa Hakko Kogyo (Japan), Sewon American Inc (South Korea) held secret meetings to fix the price of lysine, a food additive to animal feed in the 1990s.

An internal FBI informant brought the cartel down.

Attempts to Sustain Collusion II

1950s market for turbines (for electric utility companies)

A triopoly by market share:

- GE: 60%

- Westinghouse: 30%

- Allied-Chalmers: 10%

Maintained this equilibrium with clever coordination

Attempts to Sustain Collusion II

Utility companies solicit bids to build turbines:

If bid comes on day 1-17 on lunar calendar

- Westinghouse & A-C bid prohibitively high

- Ensures GE won

Attempts to Sustain Collusion II

Utility companies solicit bids to build turbines:

If bid comes on day 18-25 on lunar calendar

- GE & A-C bid prohibitively high

- Ensures Westinghouse won

Attempts to Sustain Collusion II

Utility companies solicit bids to build turbines:

If bid comes on day 26-28 on lunar calendar

- GE & Westinghouse bid prohibitively high

- Ensures Allied-Chalmers won

Attempts to Sustain Collusion II

Utility companies released their bids randomly, not according to lunar calendar

- Ensures the 60%-30%-10% distribution

Cheating by one of the 3 firms easily monitored by other 2

Nobody thought about the lunar calendar, until antitrust authorities caught on

Attempts to Sustain Collusion III

FCC Spectrum License auctions 1996-1997

Firm seeking a license in particular location (and willing to fight for it) signals to other firms via ending its bid in the telephone area code digits

- e.g. $50,100,202 for Washington DC (area code 202)

Other firms let it win (in exchange for tacit agreement to do the same)

Government-Sanctioned Cartels I

Like monopolies, some cartels exist because they are supported by governments or regulators, possibly by rent-seeking

National Recovery Administration (1933-1935)

- cartelized most industries to artificially raise prices of goods

- found unconstitutional in Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States (1935)

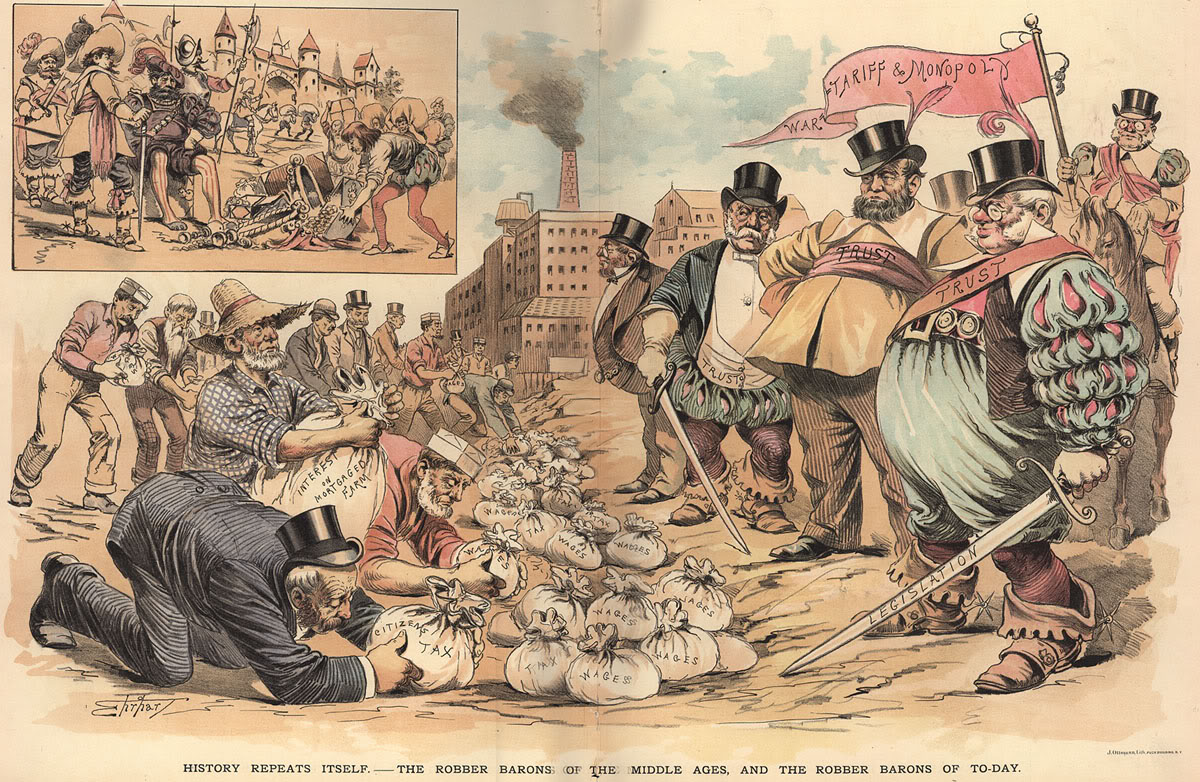

Government-Sanctioned Cartels II

Government-Sanctioned Cartels II

“[B]ecause of their inability to maintain their cartels [prior to the ICC], railroads were big supporters of the [Interstate Commerce Act] because the newly-formed ICC could coordinate cartel prices...Using the new law as authority, the railroads revamped their freight classification, raised rates, eliminated passes and fare reductions, and revised less than carload rates on all types of goods, including groceries.”

Kolko, Gabriel, 1963, The Triumph of Conservatism: A Reinterpretation of American History, 1900-1916

Government-Sanctioned Cartels III

Source: NPR Planet Money

“Marvin Horne was known as the raisin outlaw. His crime: Selling 100% of his raisin crop, against the wishes of the Raisin Administrative Committee, a group of farmers that regulates the national raisin supply. He took the case all the way to the Supreme Court, which issued its final ruling this week.”

Government-Sanctioned Cartels IV

Cartels: In Fiction I

Cartels: In Fiction II

Industrial Organization in a Nutshell

| Industry | Firms | Entry | Price (LR Eq.) | Output | Profits (LR) | Cons. Surplus | DWL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perfect competition | Very many | Free | Lowest (MC) | Highest | 0 | Highest | None |

| Monopolistic competition | Many | Free | Higher (p>MC) | Lower | 0 | Lower | Some |

| Oligopoly (non-cooperative) | Few | Barriers? | Higher | Lower | Some | Lower | Some |

| Monopoly† (or cartel)‡ | 1 | Barriers | Highest | Lowest | Highest | Lowest | Largest |

† Without price-discrimination. Price-discrimination will increase output, increase profits, decrease consumer surplus, decrease deadweight loss

‡ A cartel is n firms that act as a single monopolist, but each gets (for simplicity) 1n of the total profits.

You may find this visualization (for ECON 326) useful (interpret “Bertrand” as perfect competition and “Cournot” as oligopoly)